by Alberto J. Muniagurria and Eduardo Baravalle

The semiology of the skin is carried out through inspection and palpation successively and simultaneously. Findings should be described in terms of their location, shape, size, limits, consistency, sensitivity, relationship to deep planes, and temperature. It is important to observe if there are scratching lesions, which will lead to certain etiological causes. Lesions must be defined according to their semiological characteristics (macula, papule, blisters, vesicles, mixed, etc.).

The variety of skin color is very wide; the pink coloration depends on the hemoglobin pigment, the brown coloration of melanin, and the yellowish coloration of the collagen pigment.

This is how the color changes suffered by the patient are of great value, and not the coloration as the doctor sees it, which may be constitutional. These changes can be generalized or localized.

Observation of the skin is carried out throughout the physical examination. The first thing to see is color, looking for areas of cyanosis on the lips, nail bed, and earlobe. Cyanosis can be central or peripheral or due to methemoglobinemia and sulfhemoglobinemia. The color of the sclera should be inspected, looking for the yellow color in jaundices (the conjunctiva are not yellow in carotinemias that color the palms and soles, in pernicious anemias, during the use of quinacrine and in renal insufficiencies due to retention of urinary chromogens). The sclera can be bluish in color, as occurs in osteogenesis imperfecta. It is also possible to observe a pale yellowish coloration in anemia, or a flushing in the cheeks, as occurs in fever or in the subject of alcohol habit.

Other times, a brownish coloration is found, as occurs in Addison's disease, porphyria cutanea previa, and scleroderma, or the tan color of hemochromatosis.

Also in arsenicism there may be generalized hyperpigmentation. A grayish color of the skin can be seen in patients treated with phenothiazines, gold and silver salts. There may be generalized hypopigmentation as occurs in hypopituitarism, or in albinism due to lack of pigment in the skin, hair, and uveal tract (this disease is transmitted in an autosomal recessive manner and is accompanied by decreased visual acuity, translucency of the iris, and nystagmus ), or due to a lack of melanoforodispersing hormone, and also in myxedema.

Regional color changes can be hyperpigmented, as occurs in scurvy, pellagra, porphyria cutanea previa, chloasma gravidarum, and discoid lupus, which can evolve into hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. Other times, brown or café au lait (coffee with milk) spots, characteristic of neurofibromatosis, are seen. In Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or intestinal polyposis, periorificial melanosis is seen.

It is also possible to find blue or black spots, the size of a lentil, located on the face, neck or back, known by the name of moles. When they are distributed throughout the body, they can form the picture of progressive lentiginosis, which is accompanied by pulmonary stenosis and electrocardiographic abnormalities. Another possibility is depigmented areas or patches, or vitiligo, which are areas with irregular borders, with normal areas being hyperpigmented. Occasionally round hypopigmented lesions are observed, more frequent in summer, constituting pityriasis versicolor.

The turgidity of the skin may be reduced, as in dehydration of any etiology, in the loss of elastic fibers in old age, and in scleroderma. In Ehlers-Danlos disease, hypermobility of the skin is seen, as is Marfan syndrome. Dryness or decreased lubrication of the skin or xerosis, which is common in people over sixty years of age, is found in young people who bathe very frequently. It rarely means a deficiency of thyroid or sex hormones.

Increased temperature, as in fever or in a hot environment, or in hypermetabolic states, can increase the moisture of the skin. This can also be increased in hyperthyroidism.

The decrease in temperature can be localized, as in the insufficient arteries that present the lower limb poorly irrigated and cold, and generalized in the pictures of hypovolemic shock and in the hypothyroid and hypoglycemic coma.

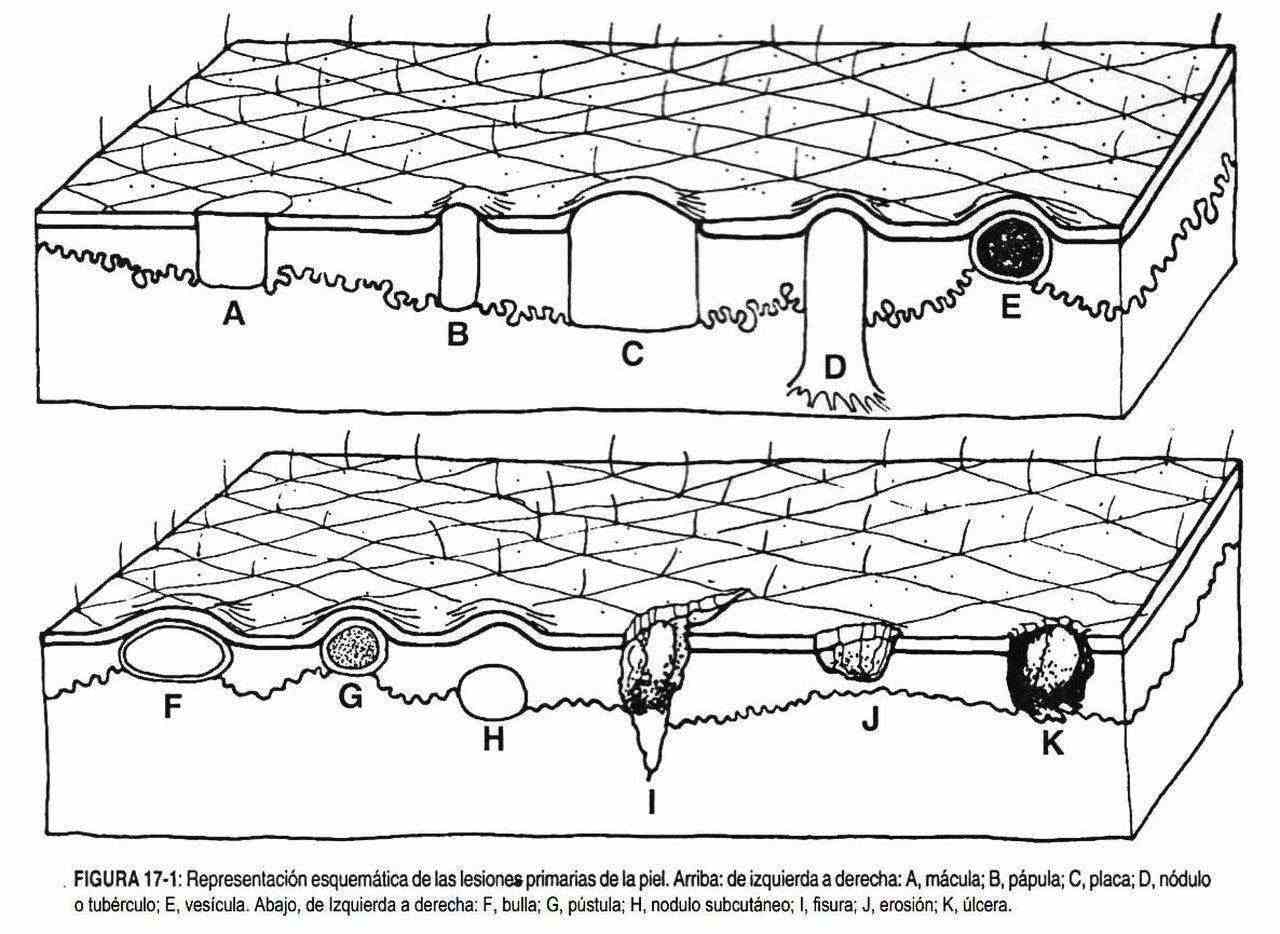

Skin lesions can be primary, secondary, or vascular (Figure 17-1). Primary skin lesions include: macula, papule, gallbladder, blister, pustule, nodule, plaque, and tumor, while secondary: erosion, ulcer, scab, scale, fissure, lichenification, atrophy, excoriation, and scars of any etiology. Vascular lesions include: ruby nevi, telangiectasia, petechiae, viper, ecchymosis, and bruising. The location, configuration, distribution and characteristics of all lesions must be described.

Skin sensitivity should be explored; leprosy is an important differential diagnosis in the presence of any macula with altered sensation.

Skin sensitivity should be explored; leprosy is an important differential diagnosis in the presence of any macula with altered sensation.

Abnormal findings on hair examination.

In the examination of the hair it is necessary to observe its distribution, quantity, color and characteristics or texture; and if there are alterations, if they are localized or generalized and if they coexist with other abnormalities.

The distribution of hair not only differs in terms of age, race and sex, but it can also be a sign of disease. The subject who lacks hair is called beardless, which has no pathological significance. Changes in the normal arrangement of pubic hair can be a sign of hormonal abnormalities, both in its production and in its metabolism.

The distribution of hair not only differs in terms of age, race and sex, but it can also be a sign of disease. The subject who lacks hair is called beardless, which has no pathological significance. Changes in the normal arrangement of pubic hair can be a sign of hormonal abnormalities, both in its production and in its metabolism.

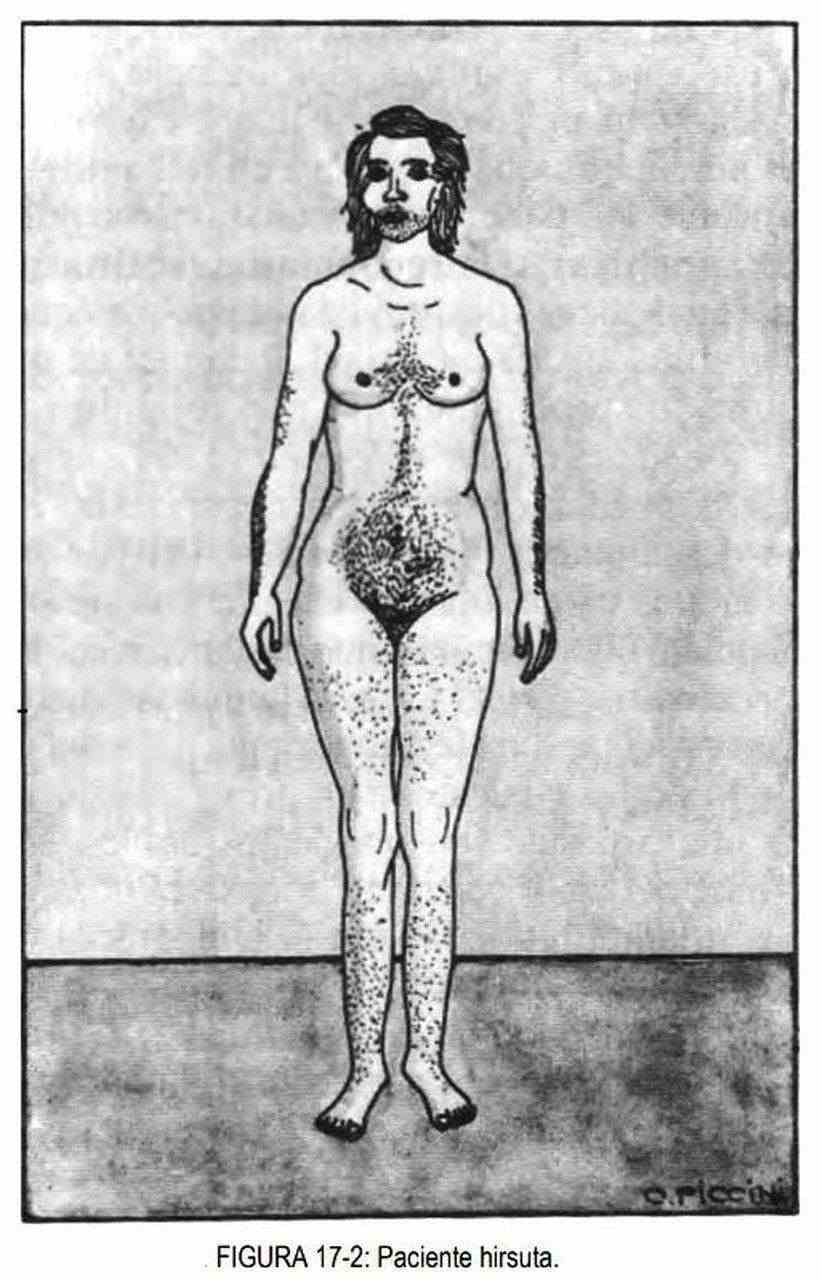

Hirsutism is the increase in hair in women, which takes on masculine characteristics (Figure 17-2).

It is a frequent reason for consulting dermatologists and internists and is due to different causes, and may be of family or racial origin. The possibility that it is secondary to the ingestion of drugs (corticosteroids, diazoxide, progestogens, minoxidil and hydantoins) must be taken into account.

Hirsute patients may show signs of defeminization (amenorrhea, decreased breast size, and loss of contours) or signs of virilization (enlarged clitoris, peeling spots, hoarseness of the voice, acne, and widening of the shoulders) (table 17-1). Defeminized hirsute women will present an increase in androgens or a decrease in estrogens. Virilizing syndromes are caused by ovarian disease (polycystic disease or Stein Leventhal syndrome, stromal hyperplasia and androgen-secreting tumors: arerenoblastoma and Krukenberg tumor) or by adrenal disease (adenomas, carcinomas and hyperplasias).

| Table 17-1. Clinical signs of defeminization and virilization | |

| Signs of defeminization | Signs of virilization |

|

|

There is also a simple or idiopathic hirsutism, where menstruation and adrenal function are normal as well as 17-ketosteroid levels.

In some poisonings by pesticides (hexachlorobenzene), a large amount of hair appears evenly distributed throughout the body, giving rise to the so-called "cute children" of the famous Turkish poisoning of the 1950s.

Alopecia, or hairlessness, can be localized or generalized (Table 17-2). In both forms of alopecia, we must distinguish those with scalp disease from those in which the scalp is healthy. Localized alopecia without scalp disease can be caused by secondary syphilis, diabetes, alopecia areata (the individual suddenly loses areas of hair, leaving an area of baldness; patients affected by this disease say that when they wake up they find a large amount of hair on his pillows and an area of baldness where the hair fell), trichotillomania (tic that prompts certain individuals to pull out their hair, eyelashes, beard and hair from armpits and pubis), or the pseudopelada of Brocq, which consists of hairless spots , little,

| Table 17-2. Classification of alopecia |

|

Localized forms with scalp disease can be observed in psoriasis (desquamative disease characterized by more or less widespread plaques of scales, of unknown etiology, whitish, resting on an erythematous base), in discoid lupus erythematosus, and in ringworms, which are fungal diseases of the scalp of which there are three types of varieties: microsporic (typical of adolescents), trichophytic, which is located in hairy or nail or hairless areas, and favic. The amantacea (false ringworm) is due to streptococcus.

Generalized alopecia without scalp disease is observed in some women who are postpartum, or after serious conditions, in thyroid disease, in alopecia totalis, in congenital hair defects, and after taking drugs, such as contraceptives , anticoagulants, chemotherapy, ionizing radiation and thallium poisoning.

Generalized alopecia with scalp disease is seen in seborrheic and contact dermatitis.

It is also possible to find areas of hair loss in some genetic disorders; Thus, for example, in myotonic muscular dystrophy, baldness or thinning of the hair can be observed in the frontal area. Waardenburg syndrome is characterized by thinning white hair with deafness, very thick eyebrows, and a broad-based nose. In another genetic disorder, porphyria cutanea late, it is possible to observe an increase in hair around the eyebrows and on the lower limbs, and in some cases the hair is harder.

In myxedema and leprosy the hair is invariably sparse and hard, dry and dull, and loss of the brow tail may be observed.

During Pediculus capitis (head louse) infection the hair is matted and covered with nits. A careful observation will show numerous lice moving among the hairs. It is common to find enlarged lymph nodes in the postauricular and mastoid areas in these patients.